Atomic Drop

“Wisdom and Knowledge shall be the stability of thy time.”

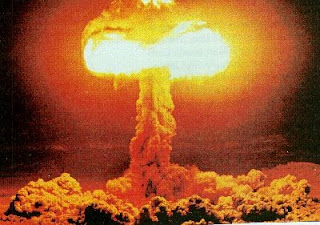

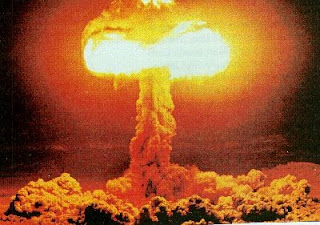

I owe my life to the atomic bomb.

It feels very strange and somewhat disconcerting to say something like that, given the horrific results of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, which killed upwards of 220,000 people, but during a recent walk through my father’s old neighborhood I found how much I owe to world’s first—and so far only—nuclear attack.

My Uncle Joe and his wife from L.A. came to stay with me last week and I took time off to accompany them as they did the New York tourist routine.

We went to Rockefeller Center, took a ride around Manhattan on the Circle Line, caught a Broadway matinee, and took a ride up to Marble Hill so my uncle could see the area where he, my father and the rest of my dad’s family grew up.

Their old apartment building is gone and I tried to imagine what the neighborhood must have looked like before the box retailers, chain stores, and bodegas, back when there was a dairy nearby that used horse-drawn wagons to deliver milk.

Standing at the bridge at 225th Street, Joe pointed to a huge rock near Spuyten Duyvil from which my father would jump into the Hudson.

As I listened to stories about my father as a young man made me wish—once again—that I hadn’t fought with him as much I did, that I had been more understanding of his experiences during the Depression and World War II.

But regret doesn’t cure a damn thing and usually makes life a little tougher.

Somewhere during our walk, we started talking about my father’s service during the war and Joe mentioned that my father’s division had been selected to participate in a planned invasion of Japan.

I remembered hearing this story years ago when I was a teenager, but I had figured that it was all talk. Yes, maybe my father might be picked to join this battle, but this invasion never got close to happening, and if it did, every U.S. soldier would be in on it.

I even joked about how I might not have been around if my father had gotten killed in the proposed attack. Or maybe he would have survived, stayed in Japan and married a local woman. I was a very imaginative kid.

But the invasion of Japan was much closer to becoming reality than I ever imagined. My uncle told me that my father’s unit had been brought back to the States from Europe ahead of other troops, and sent out to Fort Lewis in Washington to prepare for the attack.

The invasion was planned as a two-pronged assault, dubbed “Operation Downfall,” and the first part, “Operation Olympic” was scheduled to begin on “X-Day,” Nov. 1, 1945, with 14 U.S. divisions slated to take part in the initial landings.

The follow-up, “Operation Coronet,” was to begin on "Y-Day,” March 1, 1946 and it would have been the largest amphibious operation of all time. The combined cost of the two attacks was put at 1,200,000 casualties, with 267,000 fatalities.

In addition to the Japanese military, the soldiers were expected to face “a fanatically hostile population.”

“It would have made D-Day look like a picnic,” Joe said.

It’s unnerving to think that my father could have died in that invasion, or could have been seriously injured—physically, mentally, or both--or so far removed from the path his life eventually took that he would never have met my mother.

This Nearly Was Mine

My father and his fellow soldiers were worn out from fighting in Europe for so long and, like anyone else, when soldiers are tired, they make mistakes. Only in war, mistakes can be fatal.

I used to speak out against the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not knowing how important they were to my very existence. But I recall that my father denounced the bombings as well, or at least the idea of dropping two of these devices.

Joe said that my father called him when the atomic bombs were dropped and said “there won’t be any invasion now.”

Nearly 500,000 Purple Heart medals were manufactured in anticipation of the casualties for the invasion that never happened and 120,000 of these awards are still in stock. I assume they made thousands of body bags as well.

A few days later we saw South Pacific at Lincoln Center, which seems appropriate, given the World War II theme. I went in expecting an old chestnut of a story, but I really enjoyed the hell of out of thing.

We had great seats and a really cool usher who made jokes and called us all “guests.” The show has one fabulous song after another and there’s a line in “Some Enchanted Evening,” that advises you to go after your true love “or all through your life you may dream all alone.”

That line made me shiver a little, given my age and lack of a true love. I know I can’t do the old “why me?” bit, knowing how I’ve run away from potentially good relationships, stuck with disastrous ones, and spent a large part of my life completely avoiding the search for my true love.

This was my own version of “Operation Downfall.”

I think about the lease on life I got now that I know how close my father came to dying in combat and how, by extension, my family came so close to never existing. It makes me wonder if I’ve been grateful enough for the second chance we’ve been given.

My father and all those soldiers lived, while thousands of other people, many of them civilians, died or suffered terrible injuries. The bombings are more than just history to me now; they're a matter of survival.

I think those people who died in the bombings, how they many of them were just living their lives when all hell literally broke loose. They're a lot closer to me now than they were before.

I saw a TV special about the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. Everyone on the show was saying how terrible it was and how it should never happen again.

But one young Korean woman was furious at the United States for not dropping more atomic bombs on Japan.

"They should have dropped 10 or 20 bombs," she said, shaking with rage.

Her hatred was palable and shocking, in light of all the calls for peace in our time. But then the Koreans suffered so terribly under the Japanese occupation. Can you expect someone to forget all that so quickly?

The woman looked too young to have been alive during the occupation so I guess she was brought up listening to these stories. Like the song says, "you've got to be carefully taught..."

My father once told me that many years ago he heard about a new musical coming to Broadway and he had a chance to get tickets before it opened. He decided to wait and see what the critics thought and then take in the show.

That musical was South Pacific, and when the reviews came out, my father said you couldn’t get a ticket for three years. He regretted not getting those tickets when he had the chance. And we all know the value of regret.

If there's a lesson here, it would be that you should live your life, be thankful for what you have, and when you meet that stranger across a crowded room, make sure you fly to her side.

I owe my life to the atomic bomb.

It feels very strange and somewhat disconcerting to say something like that, given the horrific results of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, which killed upwards of 220,000 people, but during a recent walk through my father’s old neighborhood I found how much I owe to world’s first—and so far only—nuclear attack.

My Uncle Joe and his wife from L.A. came to stay with me last week and I took time off to accompany them as they did the New York tourist routine.

We went to Rockefeller Center, took a ride around Manhattan on the Circle Line, caught a Broadway matinee, and took a ride up to Marble Hill so my uncle could see the area where he, my father and the rest of my dad’s family grew up.

Their old apartment building is gone and I tried to imagine what the neighborhood must have looked like before the box retailers, chain stores, and bodegas, back when there was a dairy nearby that used horse-drawn wagons to deliver milk.

Standing at the bridge at 225th Street, Joe pointed to a huge rock near Spuyten Duyvil from which my father would jump into the Hudson.

As I listened to stories about my father as a young man made me wish—once again—that I hadn’t fought with him as much I did, that I had been more understanding of his experiences during the Depression and World War II.

But regret doesn’t cure a damn thing and usually makes life a little tougher.

Somewhere during our walk, we started talking about my father’s service during the war and Joe mentioned that my father’s division had been selected to participate in a planned invasion of Japan.

I remembered hearing this story years ago when I was a teenager, but I had figured that it was all talk. Yes, maybe my father might be picked to join this battle, but this invasion never got close to happening, and if it did, every U.S. soldier would be in on it.

I even joked about how I might not have been around if my father had gotten killed in the proposed attack. Or maybe he would have survived, stayed in Japan and married a local woman. I was a very imaginative kid.

But the invasion of Japan was much closer to becoming reality than I ever imagined. My uncle told me that my father’s unit had been brought back to the States from Europe ahead of other troops, and sent out to Fort Lewis in Washington to prepare for the attack.

The invasion was planned as a two-pronged assault, dubbed “Operation Downfall,” and the first part, “Operation Olympic” was scheduled to begin on “X-Day,” Nov. 1, 1945, with 14 U.S. divisions slated to take part in the initial landings.

The follow-up, “Operation Coronet,” was to begin on "Y-Day,” March 1, 1946 and it would have been the largest amphibious operation of all time. The combined cost of the two attacks was put at 1,200,000 casualties, with 267,000 fatalities.

In addition to the Japanese military, the soldiers were expected to face “a fanatically hostile population.”

“It would have made D-Day look like a picnic,” Joe said.

It’s unnerving to think that my father could have died in that invasion, or could have been seriously injured—physically, mentally, or both--or so far removed from the path his life eventually took that he would never have met my mother.

This Nearly Was Mine

My father and his fellow soldiers were worn out from fighting in Europe for so long and, like anyone else, when soldiers are tired, they make mistakes. Only in war, mistakes can be fatal.

I used to speak out against the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not knowing how important they were to my very existence. But I recall that my father denounced the bombings as well, or at least the idea of dropping two of these devices.

Joe said that my father called him when the atomic bombs were dropped and said “there won’t be any invasion now.”

Nearly 500,000 Purple Heart medals were manufactured in anticipation of the casualties for the invasion that never happened and 120,000 of these awards are still in stock. I assume they made thousands of body bags as well.

A few days later we saw South Pacific at Lincoln Center, which seems appropriate, given the World War II theme. I went in expecting an old chestnut of a story, but I really enjoyed the hell of out of thing.

We had great seats and a really cool usher who made jokes and called us all “guests.” The show has one fabulous song after another and there’s a line in “Some Enchanted Evening,” that advises you to go after your true love “or all through your life you may dream all alone.”

That line made me shiver a little, given my age and lack of a true love. I know I can’t do the old “why me?” bit, knowing how I’ve run away from potentially good relationships, stuck with disastrous ones, and spent a large part of my life completely avoiding the search for my true love.

This was my own version of “Operation Downfall.”

I think about the lease on life I got now that I know how close my father came to dying in combat and how, by extension, my family came so close to never existing. It makes me wonder if I’ve been grateful enough for the second chance we’ve been given.

My father and all those soldiers lived, while thousands of other people, many of them civilians, died or suffered terrible injuries. The bombings are more than just history to me now; they're a matter of survival.

I think those people who died in the bombings, how they many of them were just living their lives when all hell literally broke loose. They're a lot closer to me now than they were before.

I saw a TV special about the 50th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. Everyone on the show was saying how terrible it was and how it should never happen again.

But one young Korean woman was furious at the United States for not dropping more atomic bombs on Japan.

"They should have dropped 10 or 20 bombs," she said, shaking with rage.

Her hatred was palable and shocking, in light of all the calls for peace in our time. But then the Koreans suffered so terribly under the Japanese occupation. Can you expect someone to forget all that so quickly?

The woman looked too young to have been alive during the occupation so I guess she was brought up listening to these stories. Like the song says, "you've got to be carefully taught..."

My father once told me that many years ago he heard about a new musical coming to Broadway and he had a chance to get tickets before it opened. He decided to wait and see what the critics thought and then take in the show.

That musical was South Pacific, and when the reviews came out, my father said you couldn’t get a ticket for three years. He regretted not getting those tickets when he had the chance. And we all know the value of regret.

If there's a lesson here, it would be that you should live your life, be thankful for what you have, and when you meet that stranger across a crowded room, make sure you fly to her side.

Comments

War is always an ugly business and once you start down that road, it's downhill--or downhell--all the way.

Your dad sounds like quite a man. So glad he came back so we could have you.